January 28, 1077 - The Emperor submits to the Pope at Canossa

- James Houser

- Jan 28, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 1, 2021

January 28, 1077. A bedraggled man wearing a hair shirt kneels barefoot in front of a castle in the Italian Alps. He waits three days in a blizzard, freezing and starving, begging for forgiveness from the castle's guest. This man is no beggar. He is in theory the most powerful man in Europe - Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor. The man he beseeches for the opportunity to repent is Pope Gregory VII - revealed by this event to truly be where medieval Europe's power lies.

The Holy Roman Empire - a misnomer if there ever was one - existed for almost a thousand years, covering almost all of central Europe and Italy. Its Emperors, heir of Charlemagne, held the highest title in Europe but could almost never truly assert control over their scattered regions. Most Holy Roman Emperors were German, yet the powerful German dukes and nobles could defy them almost at will. No Emperor ever concentrated enough power to turn the fractured Empire into a true nation-state; by the 1400s, the Empire couldn't even be considered a unit. It would limp on as a system of laws, relationships and associations until Napoleon finally put it out of its misery.

In the High Middle Ages, though, it looked like the German Emperors might have a chance to become true centralized kings like the ones in England. They stood a better chance, at least, than the weak Kings of France. The popular misconception of Kings as virtual dictators is far from the truth; kings couldn't dream of the power even a US President holds now. They were constantly defied and outmaneuvered by powerful nobles, princes, obscure legal systems, independent cities and rich merchant associations and guilds. The biggest obstacle, however, was the Church, and it was the Church that kept the Holy Roman Empire from ever being a real power on its own.

Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, was an energetic ruler as rulers went. Unlike some Emperors, however, he had virtually no hand in the election of Popes. Popes crowned the Emperor; in essence, the Papal coronation was the source of the Emperor's power. Multiple rulers had tried to subvert this by rigging Papal elections in their favor, or simply strong-arming the Bishop of Rome into doing their will. There was a constant back-and-forth struggle between Emperor and Pope over who would be the preeminent power, especially in northern Italy.

The major dividing line between Henry and Pope Gregory VII in the 1070s was the "Investiture Controversy." (That's definitely the answer to a standardized AP History test somewhere.) Basically, the issue was who got to appoint church officials in Germany. Both Pope and Emperor wanted to do it, because both stood to gain allies and financial benefits from wielding this power. The Pope insisted it was his right as the Vicar of Christ, the Emperor believed it was his as the Emperor of Europe.

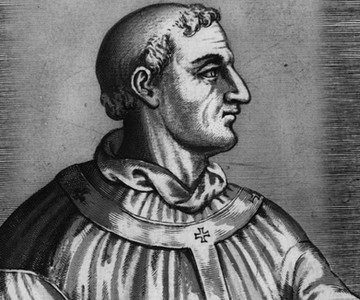

Below: Henry IV on the left, Gregory VII on the right

Things came to a head in 1076, when Henry persuaded the German bishops to declare Gregory's election invalid. In response, Gregory excommunicated Henry. As corny as this sounds, it was serious business in medieval Europe. To all Henry's subordinates and potential foes, it was open season. Anything they did to Henry or his territories was now A-OK with the church authorities, and many of them stood to gain. Henry found himself in a pickle, with major lords rising up against him all over Europe. Between a rock and a hard place, he went to the Pope.

The Pope was a guest at a castle called Canossa in the Italian Alps. Henry made his way there, dodging ambushes and pursued by his foes the whole way. Gregory refused him an audience, so Henry put the guilt trip to work. The King of Germany, Christ's Emperor, dressed up in the Biblical hair shirt and pleaded repentance for three days in the howling blizzard of the Alpine winter. On January 28, 1077, the Pope finally agreed to absolve Henry.

What does this action mean? Even if it's one of the most dramatic moments of the Middle Ages, the answer isn't clear.

It demonstrated above all the power of the Pope, a single religious leader, over someone who was in theory the most powerful man in Europe.

It demonstrated Gregory's conscience. As the Vicar of Christ, he could not deny forgiveness to one who asked for it, even if it was obviously done for ulterior motives.

It demonstrated Henry's cunning. He knew Gregory would not refuse him; despite the humiliating optics of the event, it was a political masterstroke because it removed a major obstacle to Henry's regaining of power at virtually no material cost.

Ultimately, Gregory's display of power in 1077 was not enough to save him. The German nobles refused to recognize Henry's repentance and raised a new King to replace him, but Henry defeated them in battle by 1080.

Henry once again started appointing church officials on his own terms, causing Gregory to excommunicate him once again in 1080. This time, though, Henry had suppressed his foes and was ready. In 1081, the Holy Roman Emperor invaded Italy, captured Rome, and sent Gregory into exile. He personally selected the new Pope, Clement III. Clement III, poor guy, was so hated by the Church authorities for being an "Anti-Pope" and Imperial puppet that after he died in 1100, his body was exhumed, condemned, and dumped in the Tiber River.

As for Gregory? His last words: "I have loved justice and hated inequity, and therefore I die in exile." In Italy, Gregory became a symbol of fighting back against German overlords, especially during the Renaissance and the Italian nationalist period of the 1800s.

As for Henry? His memory had a strange afterlife. He became a symbol of German resistance to Papal authority; not long after Martin Luther began the Protestant Reformation, he came to be retroactively considered "the First Protestant." When Gregory was made a saint in 1728, even the deeply Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI refused to acknowledge it. In the 1800s, Henry became a symbol of German nationalism.

So, two guys yelling at each other in the snow a thousand years ago served as symbols for the fate of modern nations.

"People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them." - James Baldwin

For Medieval Europe and a good covering of the Investiture Controversy, can't go wrong with Chris Wickham's Medieval Europe (New York: Yale University Press, 2016). For the Holy Roman Empire, see Peter H. Wilson, The Holy Roman Empire: A Thousand Years of Europe's History (London: Allen Lane, 2016).

Comments