Unknown Soldiers Episode 1 - Graveyard of Empires: Commentary and Sources

- James Houser

- Aug 2, 2021

- 3 min read

So my first podcast episode is finally out! If you're reading this, thanks so much for visiting my website and following up on the podcast. As promised in the intro to (every) episode, I will list my sources and provide supplemental images and maps here for each podcast.

I must have recorded and rerecorded (and re-rerecorded) this episode like 20 times, and I hate to say it's probably still not perfect, but it's what I've got and I think it's a very good intro. The First Anglo-Afghan War of 1839-42 is one of those things that a lot of people know happened, but they don't usually know most of the story. I usually see it mentioned in the context of "the British couldn't conquer Afghanistan, and neither could the Soviets or Americans", but it's usually left at that. Well, today I told the story as I see it.

As with any less than 90 minute presentation, there were things I left out. I had to cut a lot of context on the original Kingdom of Afghanistan, as well as Britain's initial contact with the AfghaAs n Kings. I took care of those early details in some throwaway comments early on. I also left out detail on a lot of the skirmishing that took place in 1840 and 1841.

One big factor I left out in the podcast was the presence of the Sikh Kingdom of Ranjit Singh. I made a passing reference to him as "the Indian ruler that controlled the eastern side of the Khyber Pass," the one who wouldn't let the British pass through his domain. Ranjit Singh is fascinating, and so are the Sikhs, and I really want to do an episode about them someday. But it was like an extra thousand words to explain the Sikhs' role in this conflict, so they went on the chopping block.

One guy I wish I'd had more time for was General William Nott, who commanded the British forces in Kandahar. He was actually one of the candidates to lead the British forces in Afghanistan after Keane went back to India, but the post went to no-names and eventually to Elphinstone. Nott was passed over because he, like Robert Sale, was a general in the British Indian Army and therefore looked down upon by regular British officers. Shame, too, because Nott led a whirlwind little campaign around Kandahar. Everything he did right, Elphinstone did wrong, and if Nott or Sale had been in charge at Kabul who knows what would have happened.

As for the Afghans themselves, I'm fascinated by their view of the conflict. Looking back, I wish I'd said more about how the Afghans view the 1839-42 war; their oral histories lionize Dost Mohammad and Akbar Khan to a frankly embarrassing degree. My firm opinion is that the British almost did more to defeat themselves in Afghanistan than any single Afghan leader did. Funny, that.

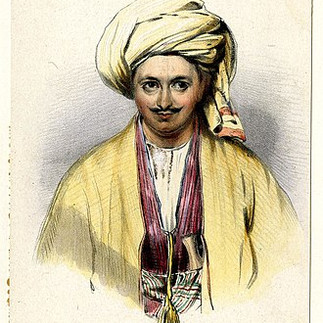

Anyway, I have pictures of most of the important figures of this podcast depicted below, followed by some maps, followed by all my sources. Thanks for listening and reading, hope you'll come back next week!

British principals, left to right: Sir William George Keith Elphinstone, Sir William Macnaghten, Sir Alexander Burnes

Afghan principals, left to right: Dost Mohammed Khan, Wazir Akbar Khan, Shah Shuja Durrani

SOURCES

Dalrymple, R. Macrory and Stephen Tanner were my main sources. Others were used for color/background/context for the most part.

Barfield, Thomas. Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Dalrympe, William. Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan. London: Bloomsbury, 2012.

Ewans, Martin. Afghanistan: A Short History of its People and Politics. New York: Harper Perennial, 2002.

Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. The Anglo-Afghan Wars, 1839-1919. Oxford: Osprey, 2009.

Hopkirk, Peter. The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia. London: John Murray, 1990.

Macrory, Patrick. Signal Catastrophe: The Story of the Disastrous Retreat from Kabul, 1842. London: History Book Club, 1966.

Macrory, Richard. The First Anglo-Afghan War 1839-42: Invasion, Catastrophe, and Retreat. Oxford: Osprey, 2016.

Tanner, Stephen. Afghanistan: A Military History from Alexander the Great to the War Against the Taliban. Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2002.

Comments